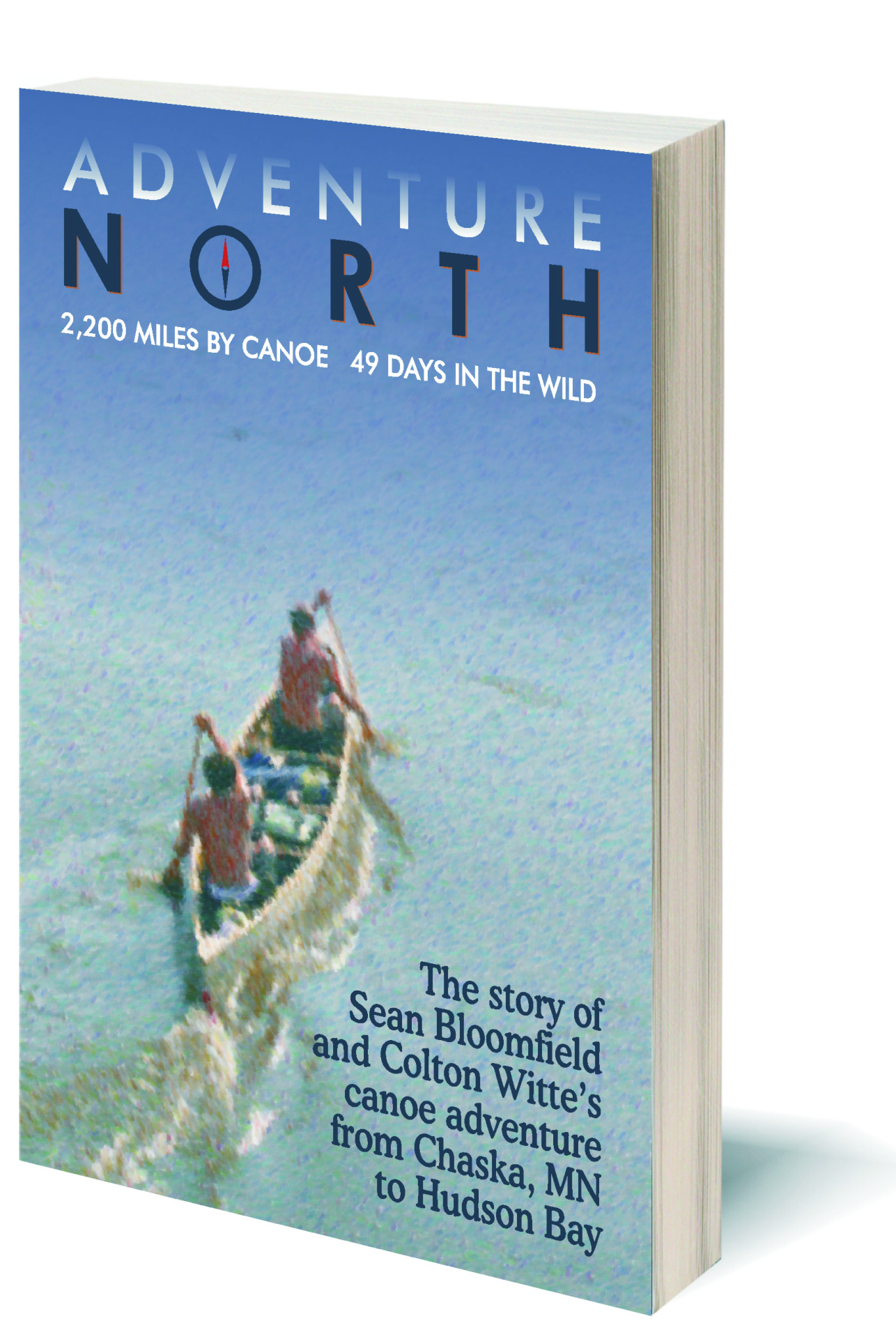

Press Kit:

Adventure North to be released September 10th

2,200 miles and 49 days in the wild.

CHASKA, Minn. – Colton Witte and Sean Bloomfield, or “The Young Paddlers,” as dubbed by the Star Tribune in 2008, captured the region’s attention by embarking on a 2200 mile canoe journey from Chaska, MN to Hudson Bay, inspired by Eric Sevareid’s book, Canoeing with the Cree. Bloomfield continues the duo’s journey in the footsteps of Sevareid by authoring their experiences in Adventure North.

In it, Bloomfield recounts the raging rapids, ocean-sized waves, and deadly Canadian wilderness that stood in the pair’s path. Adventure North is a true ‘coming of age’ story about chasing dreams, no matter how improbable they may seem. Their journey is one of authentic adventure in the 21st Century. They found it by following a boyhood dream, and aim to show that it doesn’t so much matter where you go, it’s that go.

Adventure North is due to be released September 10th, 2016 with pre-orders now available on HudsonBayBook.com. Schools, bookstores, and libraries can find information about wholesale orders at HudsonBayBook.com/for-bookstores-and-libraries.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR:

Sean Bloomfield teaches 8th grade Social Studies, and coaches high school hockey and lacrosse in Chaska, Minnesota. Along with canoeing to Hudson Bay in 2008, he and his paddling partner, Colton Witte, and two others lived off of the land for one month in the Absaroka-Beartooth region of Montana in 2011. He currently lives with his wife and son in Minnesota, and continues to seek adventure in everyday life.

For more information, Contact: admin@hudsonbaybook.com

AN EXCERPT FROM ADVENTURE NORTH:

Chapter 1

Day 46 – June 12, 2008 – Southwest corner of Swampy Lake in Manitoba

The alarm rang with unnerving normalcy. It was far too early in the morning. My slumber had begun what felt like only minutes prior. This feeling, too, had become normal. I poked my head out of the sleeping bag to investigate the source of the ear-shattering buzz. A battery-powered clock was lying directly above my head at the wall of the tent.

“4:30 A.M.” flashed mockingly in the florescent backlight. The light was totally unnecessary. Days away from the Summer Solstice and just beyond one hundred sixty miles southwest of Hudson Bay, Manitoba, so far north that polar bears outnumber people, it would have been difficult to find darkness had we wanted to.

Below the time was a small thermometer. Inside our tent, the temperature was registering in at a frosty twenty-five degrees Fahrenheit. It seemed impossible that it was June. At six feet tall and one hundred forty pounds, I was as lanky as they come, and throughout the eighteen years of my life, cold never mixed well with lankiness. This morning was not the first of our trip that I wished for several extra pounds of insulation.

My head turned and I peeked at the door to our tent. It was unrecognizable. Mosquitos, in quantities that I had once thought to be impossible, masked the screen door, waiting for the one barrier standing between them and their prey to be removed. Their thirst was understandable; less than a dozen people travel through this area each year, and human blood was a valuable commodity. We were their Thanksgiving feast.

From my sleeping bag, after my head came both hands. I gingerly removed them to inspect the damage from two days prior. Aside from the many blisters, they were visually fine. That stood opposite from the way they felt, as if on fire, every skin cell scalded by the most severe burn imaginable, caused simply by a mistaken coating of oil via our can of bear repellant. It made sense now what the rangers had told us – that bear spray could be more useful than a gun against polar bears. To be honest, if I had to pick between getting shot in the leg or sprayed with bear mace again, I would strongly consider the former.

“Alright, that’s enough out of you,” I finally groaned, tapping the button on the right side of our clock and bringing the obnoxious buzz to a halt.

Less than one foot to my left, always to my left, lay my paddling partner, Colton Witte. Unsurprisingly, his head had yet to surface from his sleeping bag. I was always the first to rise and accepted my responsibility of waking Colton dutifully.

“Colton, get up,” I said, shoving his bag with more force than necessary. Without explanation, my wake-up calls had grown in aggression as our trip progressed. Despite this, or perhaps because of it, Colton had made a habit of simply groaning and rolling over.

Giving up for the moment, I crawled out of my bag and to the door. In one swift movement, I slapped the screen to give the mosquitos a momentary shock with one hand, unzipped the door with the other, and rolled outside onto the damp soil. Only several days prior, I would have frantically escaped the swarm of bugs that were now happily making my blood the breakfast of a lifetime. Mosquito bites were now the least of my concern, and my obligatory screen-slap before opening the tent-door was the most defense I was willing to exert.

Standing up, I reached into the pocket of my raincoat for the white woolen winter hat, which was now a mainstay for the cold mornings of our expedition. Pulling it over my thick, shaggy black hair, I thought back to the day on the Red River when I had lost my first hat. Fortunately, my parents were able to bring along another one for our re-supply in Winnipeg, but I shuddered at the thought of losing a hat up here.

Though it was technically light outside, the sun was nowhere to be found. Roughly twenty feet of knee-high grass sloped its way from our tent, beneath a layer of morning frost and down to the lazy Hayes River. Resting above the water was a still, windless fog. Across the river, the land was relatively bare, having recently fallen victim to a forest fire. We were just on the edge of the fire’s reach, so several trees remained upright amidst the rubble of their fallen comrades. As I made my way to the water, my boots crunching in the stiff grass, I remarked at the eerie sensation that the fog had draped over our morning. Perhaps it was a calm before the storm ahead.

At the riverbank, I knelt down and soaked my hands in the frigid water. We heard from a group of fishermen on Knee Lake a couple of days prior that less than two weeks ago, pickup trucks were driving on the lake’s ice. While scooping the water with my palms and splashing it into my face (the closest thing to a shower in nearly a month), I wondered how long a person could survive if they swamped their canoe in these conditions.

Best not to think about it.

Breakfast was a quick, in-the-tent ordeal after Colton finally awoke, and then we were on our way. The mosquitos continued to swarm our heads and attack our eyes as we loaded the canoe and pushed off into the idle river. It regularly took several minutes for the herd of “skeeters” to lose our scent and trail off. No doubt, due to a lack of bathing, we could surely be smelled from miles away.

Just beyond our campsite, the Hayes flowed into Swampy Lake, which the two of us crossed in silent anticipation. At the far eastern end of the lake would be the start of what we called the “rapids section,” forty miles of nearly constant rapids or falls, after which we would be home free – in theory. Here, our white-water paddling would be put to the test, and after a shaky outing the evening before, I will not deny that I was at least slightly nervous.

It was Colton’s turn this morning to captain the canoe from the back, or stern. On a normal day, this meant little more than a change of scenery and slightly less legroom. Being several inches shorter, legroom mattered less to Colton than it did to me. Leading into a day full of raging rapids, though, meant he would have to be on the top of his game. The stern position was responsible for steering, and to be in control of the canoe in rapids was to be in control of our lives.

On an island at the eastern end of Swampy Lake, we took refuge from a blistering wind and steadily increasing drizzle. Here we changed out of our dry, pleasant hiking boots, and into our cold, moist neoprene boots. Normally meant for scuba diving, neoprene boots are naturally more at home in the water than your typical footwear. They provide better traction when submerged, continue to offer some small amount of insulation while wet, and they don’t retain nearly as much water. As such, dive boots worked quite well for lining, or dragging our canoe through rapids, and kept our regular hiking boots dry. Dry feet is as essential a commodity towards survival as food.

While rounding a bend at the entrance to the river, I looked longingly back at the whitecap-filled Swampy Lake. Wind is perhaps the most frustrating force of nature to a canoeist, but what was ahead for the next two days would be the greatest challenge of our lives. The immediate dangers of running rapids are obvious. Canoeists could, for instance, tip their canoe and fall out, subsequently hitting their heads on rocks, or become pinned beneath fallen branches… so on and so forth.

What was even more worrisome, however, was imagining the aftermath from tipping our canoe. We would almost surely be missing important bits of gear. If we were to lose our tent or stove, any hope of moderate comfort during the remaining journey would be killed. If we were to lose our food pack, we would have an immediate emergency on our hands. Lost paddles or a wrecked canoe… I didn’t want to think about what being stranded in these conditions would be like.

Beyond the plan-of-action type problems that would arise from tipping or wrecking, we would also certainly be risking hypothermia in the near freezing downpour. If all went according to plan, the cold and wetness that so tortured us would be limited to our extremities. Falling in, though, would wet our bodies to the core, resulting in possibly unrecoverable disaster.

I swallowed nervously and looked briefly at Colton. His sandy brown hair, normally a short buzz, had grown long and untidy. The headwind blew icy rain onto his exposed head… a final straw.

“Hold on,” he called, setting his paddle down in frustration. “I gotta bundle up some more.” On went the black and grey hat that had become such a common accessory to Colton’s wardrobe. He then pulled the hood of his orange rain jacket over the hat and zipped it up so snug that only his eyes were visible.

“Can you see?” I asked, knowing that his vision would be vital to our success.

After he nodded in the affirmative and returned his paddle to the water, I turned my head forward towards the open, seemingly innocent river ahead of me. One thing that Colton and I noticed was that the person in the bow (me at the time) always seemed to be more anxious while running rapids than the man in the stern. The bow yielded far less control of the craft. You never truly trust a friend, we found, until they’ve had your life in their hands.

“Ready?” asked Colton.

Do I have a choice? I thought, somewhat sarcastically. I paused for a moment and stared forward towards our eventual goal, one hundred sixty miles ahead: Hudson Bay. “Yep,” I said. “Let’s do this.”

EDITORIAL REVIEWS:

What could be a better tribute to Eric Sevareid than that these two delightful, adventuresome, and modest young men undertook to re-create the great broadcaster’s adolescent canoe trip from Minneapolis to Hudson Bay? As you are swept along with Colton and Sean in Adventure North, you can’t help liking these two remarkable young men as they pursue what will surely be the most important rite of passage in their lives. Now, if they use what they have learned in young manhood as wisely as did Sevareid, they might just change the world.

– Clay Jenkinson, Author of The Character of Meriwether Lewis: Explorer in the Wilderness, Bismarck, North Dakota